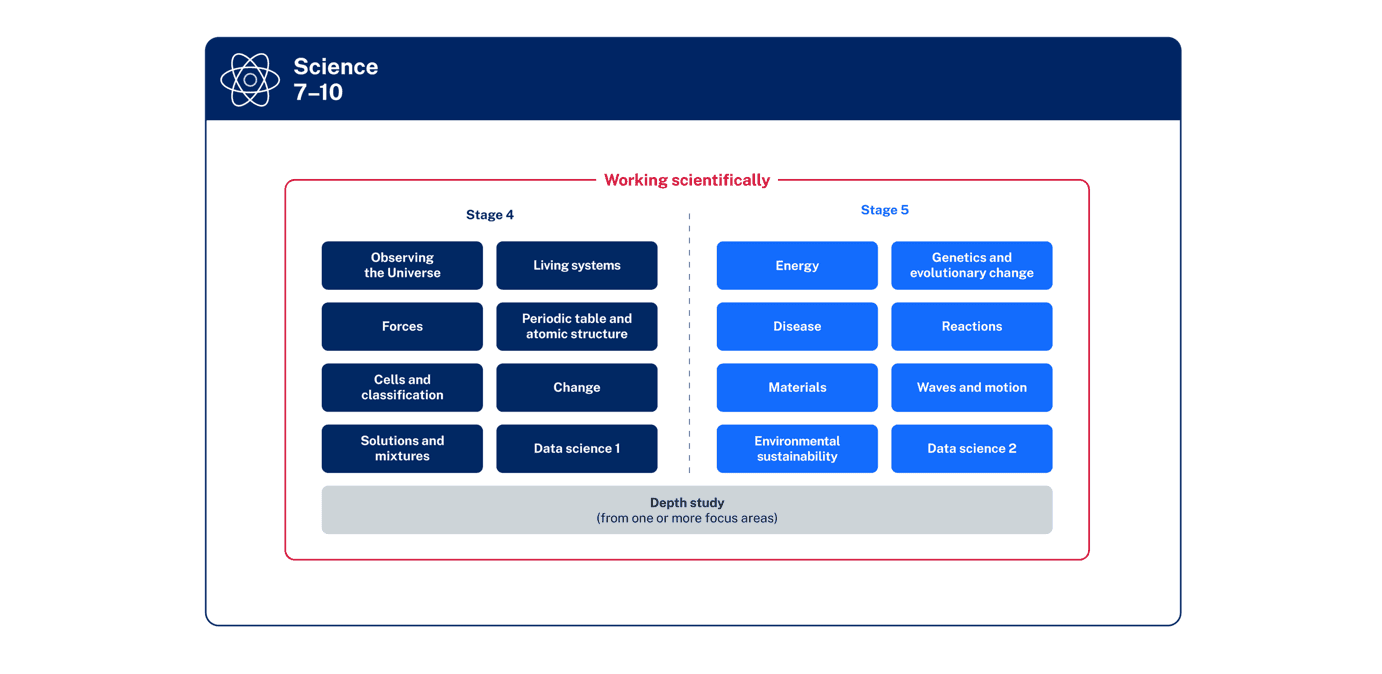

Figure 1: Working Scientifically Overview

Working Scientifically is the overarching concept in the new science syllabi produced for schools. (Although the K-6 syllabus needs to emphasise this more). If you look at the organisation of the 7-10 syllabus above you can see that Working Scientifically encompasses both the Focus Areas and Depth studies. This article is the fourth of 4 (1 each term) which I hope will help teachers that need to clarify their ideas so that the Working Scientifically skills can be integrated into science lessons. We tend to concentrate on content material rather than the skills and I hope these articles will bring a better balance so that Working Scientifically skills are developed and taught continually in science classrooms just as much as the science content. NOTE: Just because a skill is not mentioned in a Focus Area does not mean that it can’t be developed during lessons in that Focus Area.

You can revisit earlier issues of Science Education News (SEN) to recap on the articles previously published, including:

- Term 1 Observing, questioning, predicting (see SEN Vol 74 No. 1)

- Term 2 Planning investigations, conducting investigations. (see SEN Vol 74 No. 2)

- Term 3 Processing data and information, Analysing data and information. (see SEN Vol 74

Term 4: Problem solving and communicating

I would like to pose a question: How do we learn and develop a skill? If you are like me, I need to first learn the various aspects of the skill and practice each aspect several (or many!) times in order to master that particular skill so that I could perform the skill with competence. Can students learn and develop a skill with competence with just one try at a Working Scientifically skill? NO. We need to allow students to practice Working Scientifically skills over as many relevant lessons as possible so that they can become competent in that skill.

It is very important that we allow students time to develop their Working Scientifically skills as we work through the new syllabi – Primary, 7-10 and Stage 6.

In this section I refer to two resources that are available:

- NESA Teaching and Learning support Science 7-10 (2023) Working Scientifically Processes Guide See pages 20-22 for Stage 4, 35-38 for Stage 5 for these sections.

- NSW Government Education Public Schools ‘Guidelines for some working scientifically skills’ State of NSW, Department of Education, 2017 Learning and Teaching

Also most of the new text books and educational resource companies have sections on Working Scientifically which can be helpful.

Problem Solving

I find that this skill is one that I can skip over easily when teaching. Problem solving takes time and when you are trying to get through content this skill can be left behind. Also, we tend to give students ‘recipe’ types of investigations that don’t give much time for students to complete (or problem solve!). If problem solving is introduced, then it takes time. Even when getting students to repeat an experiment if it didn’t work well, we tend to push them along to the next activity! This is not in the spirit of solving a problem!

I was thinking about a problem that I was trying to solve over the last few weeks. I had a visor in my car that kept dropping. Rather than getting another one, how could I solve the problem? I used gaff tape (of course) to put around the areas that were slipping but to no avail. It took me a couple of weeks putting up with it dropping down again when I thought of double-sided tape but not really a good result. Then an idea! I get these fridge magnets in the mail. Put them together with double sided tape on the outside of the magnets. It worked! Until it gets hot and the glue on the tape gets weaker. So, more thinking. The process of problem solving takes time and an understanding of concepts and how they can be applied. This skill needs to be developed in all students no matter if they continue in science after Year 10 or not.

Critical thinking is the overarching cognitive ability to analyse, evaluate, and form judgments about information, while problem-solving is a specific process of identifying a challenge and finding a solution to it. (from Google AI)

I have just read ‘the matter of everything twelve experiments that have changed the world’ by Suzie Sheehy. It is an excellent example of problem solving in nuclear physics research over the past hundred years. Most of the early researchers had to make their own apparatus to try to solve the problem they were working on. This took critical thinking, engineering skills and the ability to problem solve in order to achieve an experimental outcome.

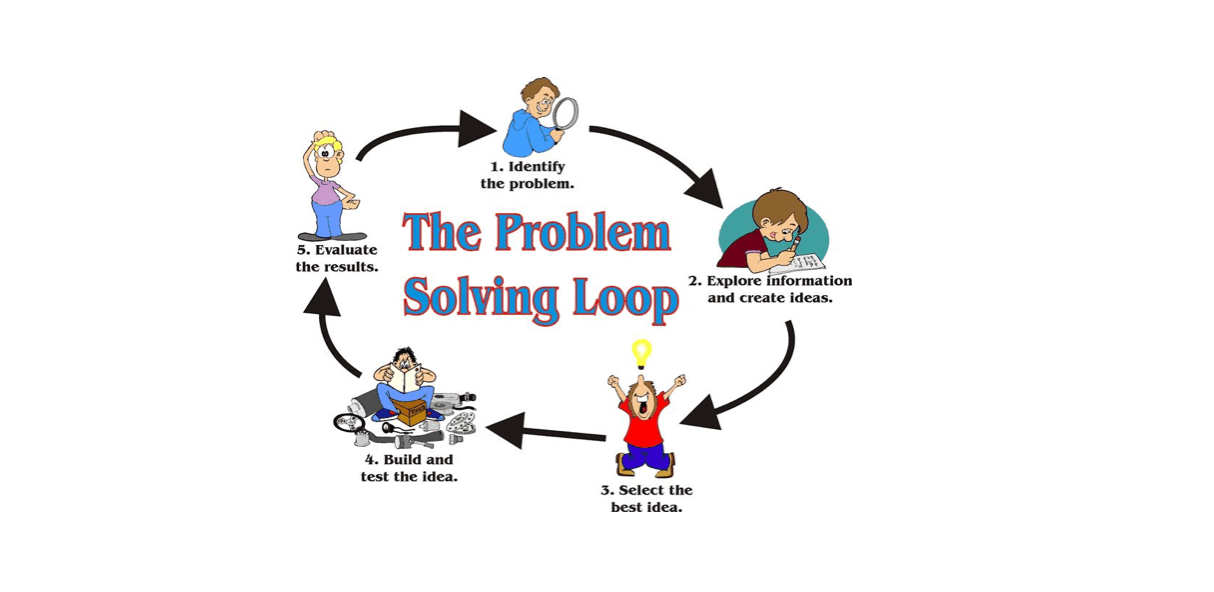

Figure 2: This diagram gives a simplified process for problem solving.

Another way to approach problem-solving is to understand the problem, obtain science knowledge about what might help, think about how the problem will be solved, try out your ideas, review how the experiment went, talk or write about how your solution solved the problem, learn from your experience. You may need to try again to obtain a better outcome. (adapted from Pearson Working scientifically toolkit)

Stage 4 Outcomes

- Identify problems and devise possible strategies or solutions

- Use identified strategies to suggest possible solutions to a familiar problem

- Use given evaluation criteria to select optimal solutions to problems

- Identify cause-and-effect relationships and develop models to explain phenomena

- Evaluate the suitability of different strategies for solving an identified problem using given criteria

As an example, let’s use my problem about the sun visor above to work through these outcomes.

Identify problems and devise possible strategies or solutions

In Science we say ‘to investigate ….’, or ‘to find out ….’ as an aim for an investigation which will help solve the problem. We then can form a hypothesis or an ’educated guess’ as to what might happen in that investigation.

Problems need to be thought about and solved! In science we can ask questions to start the thinking process like ‘How can an egg be dropped from a height without breaking?’ or ‘Can we keep koalas from becoming extinct?’ or ‘How can we recycle soft plastics?’ Once the problem is identified then the thinking process begins. The process now is to think about how the problem can be solved (the strategy)/how to find an answer to the problem. You can relate this to Mathematics especially word problems!

My problem: the sun visor is loose and drops down at the wrong time.

Possible strategies/solutions: get a new one, get one from a wrecker or put some gaff tape on the places that hold the visor up.

Use identified strategies to suggest possible solutions to a familiar problem

A familiar problem in Stage 4 could be how to separate a sand, sugar and water mixture. Just from a student’s everyday experiences they could come up with some strategies to solve the problem of separating that mixture.

Once strategies are identified about how to solve a problem think about those ideas: what dissolves, can a filter be used, how can water and sugar be separated

My problem: buy a new visor – costs money, obtain one from the wrecker – costs less money, gaff tape on the parts – have gaff tape that will increase the friction on the parts that move.

Use given evaluation criteria to select optimal solutions to problems

This outcome is designed for students to find the best (optimal) solutions to the problem they are trying to solve.

Note that in Stage 4 the evaluation criteria should be GIVEN so that students can select the best strategy to solve their problem. This needs to be scaffolded for students at the beginning of Stage 4 and gradually let students increase collaborative or individual problem solving towards the end of Stage 4 so they can develop their evaluation criteria.

Evaluation criteria are aspects of a project that will give it quality such as:

- Accuracy - The extent to which a measured value agrees with its true value (that is - reference value),

- Precision - The extent to which multiple measurements, made under identical or similar conditions, agree with each other,

- Reliability - The extent to which the findings of repeated experiments, conducted under identical or similar conditions, agree with each other.

- Validity - The extent to which an experiment addresses the question under investigation.

See this resource: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/science/science-curriculum-resources-k-12/science-11-12-curriculum-resources/evaluating-scientific-data

Evaluation criteria for a science project could also be: Does it cost too much, are materials available, will the materials last for the entire project, can measurements be made accurately, etc.

In reality, I look at this as advice that I might give a student when thinking about a Depth Study problem for the new syllabi or the Student Research Project in the past years.

Identify cause-and-effect relationships and develop models to explain phenomena

What does cause and effect mean? A cause-and-effect relationship in science is when one action causes something to happen. This type of thinking is important to science and is why we can identify independent (IV) and dependent (DV) variables. Examples are

- “a plant grows bigger with when fertiliser is applied: cause - fertiliser applied, effect – plant grows bigger.

- ‘when an acid and base are combined, salt and water are produced’: cause – acid and base combined, effect – salt and water are produced.

- ‘when a force is applied a stationary object will move’: cause – force is applied, effect – an object moves

- ‘an earthquake occurs when the earth’s tectonic plates move’: cause- tectonic plate movement, effect earthquake

Note: the independent variable is the cause and the dependent variable is the effect so as heat (IV) in a kettle is increased the water temperature (DV) increases. (IV-independent variable, DV dependent variable)

Development of models to explain the cause-effect relationships enables students to visualise the relationship. For example: kicking a soccer ball or using states of matter to show the particle arrangements. A model could be planned and designed by students to illustrate the tectonic plate movement resulting in an earthquake. This would be a good problem to work on.

Evaluate the suitability of different strategies for solving an identified problem using given criteria

Again note the words GIVEN criteria. Students need to be able to evaluate (make a judgement) any strategies being used to solve a problem, given a set of criteria.

For example: if I wanted the solution to my visor problem to be cheap in cost then buying a new one is not suitable for my problem but if I have some large fridge magnets that I got in the mail for nothing then they are suitable to try to solve my visor problem because they have been obtained with no cost!

Stage 5 Outcomes

- Select suitable strategies and implement them to solve an identified problem

- Develop evaluation criteria relevant to identified problems

- Assess the solutions proposed based on the relevant evaluation criteria

- Use cause-and-effect relationships and models to explain ideas and make predictions

- Evaluate different approaches used to solve problems

- Evaluate claims using scientific knowledge and findings from investigations

These outcomes are based on the skills in problem solving developed in Stage 4. They call for less scaffolding, more personal/collaborative problem solving and less guided development of these critical thinking skills.

Select suitable strategies and implement them to solve an identified problem

Note: the verbs ‘select’ and ‘implement’ relating to strategies to solve a problem. When a problem is identified the team/individual needs to research possible solutions.

This requires students to be able to select resources that are suitable and reputable. This requires that the resource is written/published recently about the topic, that it is relevant to the problem, that a person that wrote it is qualified, that the information is correct and reliable and the reason that it was written i.e. is it biased to one view of the problem.* It is important that students realise the importance of this process because looking for social media and AI sites is not going to give reliable and reputable resources for strategies to solve a problem being investigated. *(This is a summary of the California State University ‘CRAAP’ test.)

Once resources are selected then the strategy/strategies can be tested to see if the problem can be solved.

Develop evaluation criteria relevant to identified problems

This requires students to develop their own evaluation criteria with the skills developed in Stage 4. These criteria need to have clear descriptions. Note: the aspects of evaluation criteria in the Stage 4 outcome above.

Assess the solutions proposed based on the relevant evaluation criteria

This assessment of the solutions proposed requires students to find out the limitations and advantages of those solutions to solve the given problem. The evaluation criteria developed for the problem being investigated need to be very clear as to their suitability for the solution of the problem.

Use cause-and-effect relationships and models to explain ideas and make predictions

Understanding the cause-and-effect relationship developed in Stage 4 is important for students to be able to explain an idea. Students should also be able to use models of these relationships to not only explain but also make predictions about an idea.

Evaluate different approaches used to solve problems

Evaluate means to make a judgement or find the value of different approaches to a problem. This includes being aware of different ways to approach a problem or solve the problem. This requires researching reputable sources to find different approaches to a problem or asking for ideas from others involved in the problem being investigated.

Evaluate claims using scientific knowledge and findings from investigations

When students are researching for a project or investigation, judgements are required by a student or team of students about claims made when researching about that particular topic. These judgements need to be evaluated through use of scientific knowledge and making sure that any claims are from reputable sources and have included relevant investigations about the topic.

Communicating

NESA Advice on writing Science 7-10 can be found here: https://curriculum.nsw.edu.au/file/fe1076ee-9ac2-48d9-b0e4-cb1f2d51799e/science-7-10-2023-advice-on-writing.docx

Stage 4 Outcomes

- Present findings and ideas in a range of communication forms, including using relevant scientific terms, diagrams and graphical representations, as appropriate to audience and purpose

- Create written texts to communicate scientific concepts, ideas or investigations using conventional scientific text structures

Present findings and ideas in a range of communication forms, including relevant scientific terms, diagrams and graphical representations, as appropriate to audience and purpose

Present findings indicates that an investigation has been done. These findings could be observational, experimental or a combination of both. Thus, findings might need to be expressed in various forms as indicated in the outcome. If you are observing a flower or a cell with a microscope, then a labelled diagram is a good way to communicate the findings. If the investigation is experimental then findings need to be written and/or tabulated, then graphed which can then be communicated by interpretation of the data. Appropriate to audience and purpose in Stage 4 indicates the need to explain and idea/findings of an investigation to a teacher or peer group that you understand the concept and processes in an investigation. This is also important in tests/assessments so that a marker knows the writer understands relevant scientific terms and ideas in a test question. Assessment questions that incorporate these skills are important for Stage 4 students to learn for the future.

Create written texts to communicate scientific concepts, ideas or investigations using conventional scientific text structures

In Stage 4 we want to develop the student’s ability to present findings and information in a basic format of a science report. A discussion and clarification of variables: independent, dependent and controlled, needs to be done before the aim is written. It is important to clarify these terms.

In my school we use the following headings:

Aim: What do we want to find out in the experiment? This needs to include the independent and dependent variables e.g. To investigate the effect of the amount of fertiliser on plant growth.

Hypothesis: A proposed explanation of a possible result/trend in the investigation. This is written before the experiment. Example: A plant will grow faster when more fertiliser is given to the plant.

Materials: List of ALL apparatus, chemicals and materials needed with the specific quantity and size e.g. 1 x 250 mL beaker, 1 x roll of sticky tape

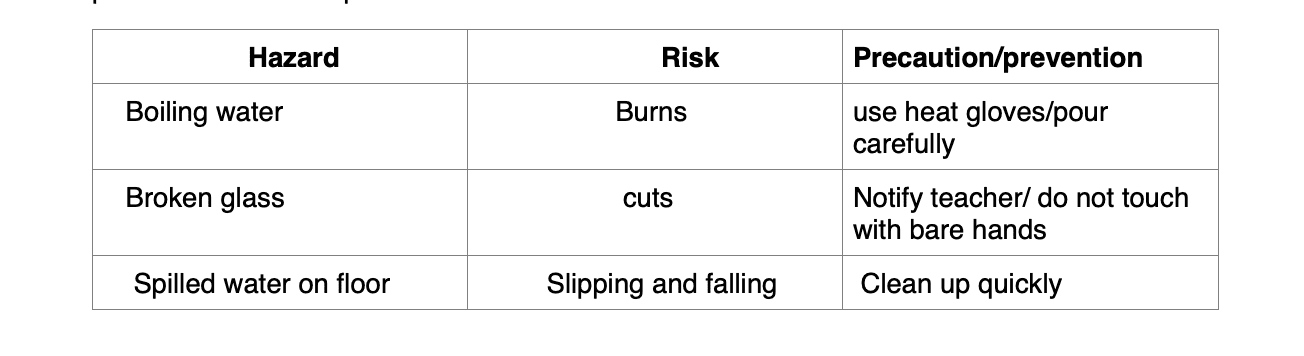

Risk assessment (safety): All possible hazards (what can cause harm/injury), risks associated with the hazard (what are the possible injuries) and precautions to mitigate/prevent the risk. We put it in a table.

Method: This a numbered, logical step by step process that can be followed by anyone else. It is written in third person and past tense e.g. 4. 10 mL of water was measured using a 10 mL measuring cylinder and poured into a test tube.

I find that it helps for students to show their method to one or two other students and have them feedback on any parts they are unsure about if they were to do the experiment.

Results: This where the data that is collected (raw data) is placed into a results table. It can be qualitative (numerical) or qualitative (non-numerical) data depending on the investigation. Averages need to be calculated if the experiment is done more than once. It is good to do the experiment at least 3 times to make it more reliable. A graph should also be constructed using the average data. For the plant/fertiliser example above 3 parallel experiments using the same method could be set up. Also, in a class 6 groups could do the same experimental setup and the data could be gathered and averaged and then graphed using the average data.

Discussion: This is a very important section as it should explain any trends in the results, identify any errors in the procedure and suggested improvements to the investigation. It is important in the discussion that the scientific concepts and terms in the investigation are explained and related to the results. This section should also discuss the accuracy, reliability and validity of the investigation and any aspects that could be improved for these criteria.

Conclusion: This is a statement of whether the aim has been supported or not supported using the variables. This statement does not ‘prove’ but it supports or does not support the aim. Any reasons for the statement needs to be placed in the discussion.

Bibliography: (if necessary) This done using the criteria of your school. But it needs to emphasised that all information collected in research needs to be placed in this section in bibliography form.

As we move into Depth Studies in each year of Stage 4, it is going to be important that students learn how to communicate concepts, ideas and results of investigations in written form. This does not mean only scientific reports but also written explanations of scientific ideas such as how tides are formed or how eclipses occur. This can be done in diagrams, but student understanding can also be gauged by a written explanation. We have all read responses to test questions that require students to communicate their understanding and have thought ‘where did that come from’!!

The NESA Advice on Writing document for Science 7-10, referenced above, gives some ideas for helping students complete a written explanation as well as an investigative report.

Stage 5 Outcomes

- Present scientific arguments using evidence, correct scientific language and terminology, as appropriate to audience and purpose

- Create written texts to communicate scientific investigations, explain scientific theories and principles, structure a scientific argument, and evaluate findings in light of scientific knowledge

- Recognise that scientific texts develop arguments by encouraging the reader to adopt a specific perspective and positioning them to accept the authority of a text

The NESA Advice on Writing document referenced above has information for Stage 5 on communicating a scientific argument, synthesising research notes and developing a discussion in a practical report.

Note: in each of the outcomes for Stage 5 the idea of scientific arguments is included. This indicates that opportunities (such as a Depth Study) need to be developed so that students learn how to present a scientific argument.

Present scientific arguments using evidence, correct scientific language and terminology, as appropriate to audience and purpose

This outcome asks for students to present scientific arguments based on evidence with science terminology and language that is correct. This requires students to understand the concepts being presented. Again, this requires students to write for the intended audience (examination!) and knowing the purpose of the argument

e.g. the difference between different types of cells or to argue for a certain action to limit climate change.

Create written texts to communicate scientific investigations, explain scientific theories and principles, structure a scientific argument, and evaluate findings in light of scientific knowledge

This is based in the Depth Study. It requires research and putting together an argument based on the research and investigations for that particular science concept. Students are required to create written texts to communicate what has been investigated using known theories and principles. A scientific argument then needs to be structured, and an evaluation of the investigation presented. I would practice each aspect individually:

- Explain scientific theories and principles

- Structure a scientific argument

- Evaluate findings in light of scientific knowledge

Then students can begin to create a written text to communicate about a scientific investigation by combining these skills.

In Stage 5 these written texts need to be structured through Years 9 &10 in order for Year 10 students to produce written texts individually based on their ability.

Recognise that scientific texts develop arguments by encouraging the reader to adopt a specific perspective and positioning them to accept the authority of a text

This outcome is based on students being able to evaluate secondary sources as to their relevance to the concept being researched. See the information below about the ‘CRAAP’ test (California State University) to evaluate a secondary source.

- Currency: Make sure the resource is written/published recently about the topic,

- Relevance: that it is relevant to the problem,

- Authority: that a person that wrote it is qualified,

- Accuracy: that the information is correct and reliable and

- Purpose: the reason that it was written i.e. is it biased to one view of the problem

Note that it is important that sources have been peer reviewed and the hypothesis of the research tested by scientists. The biggest aspect of secondary sources is evaluating to see if they are ‘biased’ in their presentation of information about the concept. Thus, several sources need to be reviewed for comparison of viewpoints and research results.