Many students enjoy learning about science yet still do not see themselves as “science people” (Lei et al., 2019). The question “Are you a science person?” is a powerful one. It reveals how individuals perceive their connection to science and whether they feel science is relevant to their lives. This sense of identity can be understood through the concept of science capital.

First introduced by researchers at King’s College London (2015), science capital refers to the accumulation of science-related knowledge, attitudes, skills, and experiences that shape how a person engages with science. It provides a framework for understanding why some individuals feel confident and connected to science, while others do not. Science capital includes:

- What a person knows about science,

- How they think about science,

- The science-related activities they take part in, and

- Who they know that works in or with science.

A student’s level of science capital influences whether they answer “yes” or “no” to the question, “Are you a science person?” Those with high science capital are more likely to identify as science people, while those with lower science capital may see science as distant or inaccessible. Although schools are only one contributor to science capital, classroom experiences play a crucial role in shaping students’ science identities and influencing future STEM aspirations.

Generating a shared experience at the beginning of a new teaching sequence can strengthen the collective science capital of a class. Shared experiences provide all students, regardless of background, with a common foundation from which to discuss and explore scientific ideas. This approach is particularly valuable for students with lower science identity, as it establishes a more equitable starting point. When students engage in a collective, hands-on experience, they are better able to connect personally to the science, express their ideas confidently, and participate meaningfully in class discussions. A shared scientific vocabulary also enhances clarity and inclusion, helping students articulate and refine their thinking (Ainscow, 2020).

Sourced from Australian Academy of Science

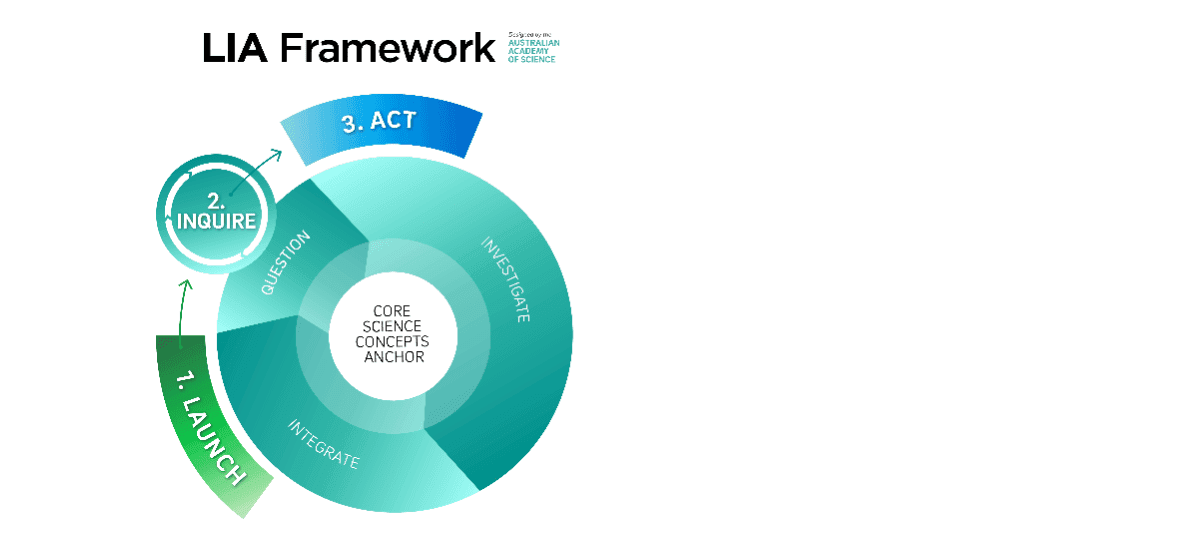

Primary Connections has embedded this understanding within its Launch, Inquire, Act (LIA) Framework. Each phase consists of a set of teaching routines that help educators adapt or design science learning sequences. Within the Launch phase, the “Experience and empathise” routine invites teachers to begin with an activity that promotes equity and shared understanding. This routine allows students to start with an accessible, familiar experience, reducing the advantage that prior science exposure or technical vocabulary might otherwise confer.

For instance, in the Year 5 Primary Connections sequence Wear on Earth, students begin by exploring the local area to observe which surfaces that may have experienced weathering or erosion. This “Experience and empathise” activity often sparks natural curiosity and discussion: Have you seen this before? Why are some areas more likely to ‘wash away’? How might this change throughout the year? These shared observations become the foundation for later lessons on how the interactions between Earth’s systems cause continuous change - the core scientific concept.

By anchoring new learning in everyday experiences, such approaches validate all students’ ways of knowing and make science more relatable. When students can connect a scientific idea to something they have personally experienced, they are more likely to see themselves as capable participants in science. In this way, building science capital becomes not only about what students know but also how they see themselves in relation to science.

Ultimately, when teachers create inclusive, experience-based learning environments, more students can confidently answer “Yes, I am a science person.”

Primary Connections teaching sequence: Year 5 Wear on Earth

Lesson 1: Experience and empathise routine

Identifying local issues

Take students on an observation walk of the school grounds or local area to look for examples of weathering and erosion. Alternatively use Google Maps to take a virtual tour of your local area. See the embedded professional learning Using Google Maps to undertake a virtual tour for more information.

Before the walk/virtual tour

Ask students if they can identify any school/local examples where weathering and erosion might have taken/be taking place. Discuss what kinds of places in the local community are likely to be more vulnerable to weathering/erosion and the factors that make them so.

Allow students the opportunity to share ideas of how they might identify sites of weathering and erosion before offering any ideas.

Some examples you might use as prompts, if required, include:

- in coastal communities, exposed sand dunes are vulnerable to high winds and tides, particularly during and after heavy rainfall.

- in rural communities, fields and paddocks are vulnerable after harvesting or due to grazing livestock.

- river and lake shorelines are vulnerable after heavy rainfall events.

- local parks and bushlands might have pathways worn by heavy pedestrian traffic, both human and animal.

- buildings can also show signs of weathering including peeling paint, cracking materials, or worn-down stones, pavers or bricks.

During the walk/virtual tour

- Stop at student-identified sites of potential weathering and/or erosion.

- Discuss what made the student/s want to stop and explore/discuss this particular site.

- Identify the factors they think are present that indicate weathering and/or erosion.

- Take photographs/videos of sites of interest.

- Mark sites of interest on a map of the local area.

- If you have already identified a weathering/erosion issue in your schoolyard or local area that your students will design a solution for, ensure this area is visited on the walk/virtual tour and discussed in depth after the walk.

After the walk/virtual tour

- Review the photographs/video and location of sites of interest and why students wanted to observe them more closely.

- Identify the features that made this site susceptible to weathering/erosion.

- Discuss how the environment, including the who (people) or what (plants and animal) might have been changed by the weathering/erosion.

- Discuss if students think that human activity has contributed to the weathering/erosion and how.

- Discuss if students think these changes are problematic and potentially need to be controlled.

- Discuss what might happen if the erosion is not controlled.

Explain to students that at the end of the sequence, they will have an opportunity to design (and possibly test) a strategy to address a problem caused by weathering or erosion in the community.

References:

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: lessons from international experiences. Nordic journal of studies in educational policy, 6(1), 7-16.

- King's College London. (2015). Science Capital – an introduction [YouTube Video]. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A0t70bwPD6Y

- Lei, R. F., Green, E. R., Leslie, S., & Rhodes, M. (2019). Children lose confidence in their potential to “be scientists,” but not in their capacity to “do science.” Developmental Science, 22(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12837