Yasmin, Jade and Alexis are pre-service primary teachers in their final semester of the Bachelor of Primary Education at the University of Sydney. This article examines embodied learning as an innovative pedagogical approach for making complex scientific ideas more accessible in primary education. Focusing on the topic of Earth and Space in Stage 2, we illustrate how teachers can employ embodiment involving active participation to deepen students' conceptual understanding of the Solar System.

Embodied Learning

Embodied learning refers to the idea that cognition and understanding are deeply connected to the body’s interactions with the world (Way et al., 2021; Wilson, 2022). This method challenges the idea that learning is just mental— it involves movement, gesture, and touch, aligning with the embodied cognition theory, which says “thinking is grounded by physical experience” (Wilson, 2002). Movement can help students improve memory and understanding by creating richer, multisensory learning experiences. Such activity is especially helpful in upper primary science, where complex ideas like energy or forces become perceptible (Lindgren & Johnson-Glenberg, 2013; Shapiro & Stolz, 2019). Embodied learning is effective in connecting abstract ideas to real bodily experiences to make it concrete, thus making it a powerful tool in science teaching and learning.

Syllabus Outcomes and Content

The following outcome and content points from the NSW Science and Technology syllabus (NESA, 2024) are the focus of this article.

- ST2-SCI-01 - uses information to investigate the solar system and the effects of energy on living, physical and geological systems

- Describe features of our solar system using multimodal representations

- Modelling Earth’s revolution around the Sun and recognising that a complete revolution takes 365.25 days

Figure 1: Equipment List

Description of Learning Sequence & Teacher Procedures

At the beginning of the lesson, students are introduced to the key vocabulary on word cards, including terms such as seasons, axis, day and night, rotation, orbit and revolution. To build on prior knowledge, students use turn and talk partners to discuss the meaning of these words. Students then share their answers in a class discussion, which also recaps the features of each season.

Students then observe a teacher-led demonstration in which a globe (representing the Earth) is rotated while a torch (representing the Sun) illuminates it. This allows students to visualise how the Earth’s rotation produces day and night, as well as how in revolution, its orbital path around the Sun results in seasonal variations.

To further consolidate their understanding of the Earth’s movements, students engage in an embodied learning task in pairs. The teacher calls out the new vocabulary terms, rotation, orbit and revolution. Students physically model the relationship between the Sun and Earth by role-playing Earth’s rotation, spinning on its tilted axis and its revolution by following an orbit around the Sun. Each student wears a headband with a planet attached, reinforcing the identity of the celestial body they represent, while the student acting as the Sun also holds a torch to simulate sunlight. Students take turns swapping roles to experience different planetary movements.

Figure 2: Planet headbands

The activity is conducted over approximately 10 minutes to maintain engagement and ensure all students participate. During the activity, emphasis is placed on the duration of each movement, highlighting that rotation takes one day (24 hours) and revolution takes approximately one year (365 days). Music is incorporated as a supplementary tool to reinforce this, with faster rhythms representing rotation, while slower rhythms indicate revolution. The teacher observes students’ representations to assess understanding and asks some groups to perform their modelling of the Earth’s revolution, rotation and orbit path.

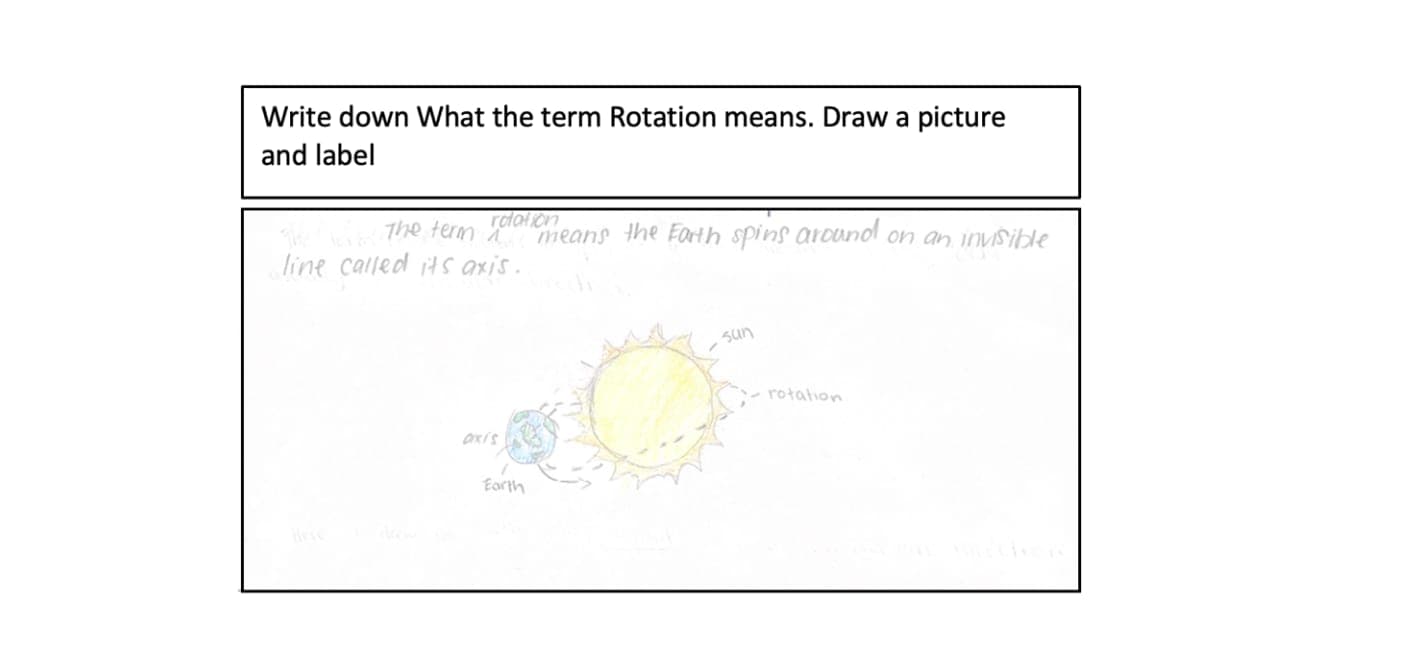

Further evidence of student understanding is assessed via a worksheet which asks students to write and draw how the Earth’s Orbital revolution and rotation show consolidation of concepts learnt from the overall lesson and specifically from embodied learning activity.

Figure 3: Rotation sample student response

Figure 4: Orbit sample student response

Figure 5: Revolution sample student response

Safety Procedures

Teachers need to be aware of potential risks when including embodied learning in lessons and take steps to ensure student safety, such as:

- managing student behaviour to maintain safe movement

- ensuring adequate space is available for students to move their bodies

- keeping areas clear of furniture to prevent collisions, tripping, or falling

- conducting lessons outside or in larger classrooms when possible

- reminding students of behaviour expectations, including:

- safe movement

- avoiding rough play

- showing respect and awareness of others (AERO, 2023; Dolan, 2015)

Pedagogical Justification

The sequence is designed to integrate multimodal representations like a text, diagrams, models written and verbal explanations alongside the pedagogical strategy of embodied learning. It is important to acknowledge that embodied learning is not positioned as the core objective of the lessons but is instead employed as a pedagogical tool to support students’ comprehension and engagement of the content. By incorporating gestures, enactments and whole-body movements, students' understanding can be strengthened, which is crucial in order for them to build on prior knowledge and progress effectively in their learning (Mavilidi et al., 2023; Luo et al., 2025). Through this enactment, students experience the movements and relationships of the Sun and Earth kinaesthetically, observing and embodying concepts such as Earth’s orbit, rotation, revolution into bodily memory to strengthen comprehension (Luo et al., 2025). Role-play like these further fosters emotional and physical engagement, while the corresponding gestures map movements to conceptual understanding in dynamic ways (Luo et al., 2025).

Moreover, the lesson engages students through immersive, sensory-rich experiences, guiding them to explore and represent scientific concepts through embodiment and multimodality. This supporting them to evaluate and synthesise their knowledge through reflective and comparative tasks (Lindgren & Johnson-Glenberg, 2013; Shapiro & Stolz, 2019).

Throughout the lesson, students are encouraged to work together to explore and represent what concepts like Earth’s rotation and revolution would look like. This peer-learning process encourages students to critically engage with each other’s interpretations and deepens understanding through collaborative dialogue. This strategy helps build students’ confidence in using new scientific terms while also clarifying their ideas through peer conversation, promoting both conceptual understanding and communication skills in science (Hindman et al., 2022 ; Walter, 2018).

The use of open-ended and probing questions throughout the learning experience helps teachers to elicit prior knowledge, assess students’ understanding (Myhill & Dunkin, 2005). Teachers are encouraged to ask challenging questions that sparks curiosity which enables children to draw from and connect prior knowledge to new concepts (Hattan & Alexander, 2020). Asking comparative questions enables students to reflect on their learning experience and provides teachers valuable formative assessment data by communicating understanding and common misconceptions (Karaman & Buyukkidik, 2023). Additionally, it also portrays the students' engagement with embodied learning strategies which closes the loop between embodied activity, verbal reasoning, and written multimodal representation.

Questions to Guide Children’s Observations and Stimulate Thinking

Reflection on Use of the Learning Experience

The sequence positively impacted student learning and engagement. Students produced pleasing results and demonstrated an improved and more sophisticated understanding of rotation, revolution and orbit. The embodied nature of the lesson also increased students' motivation to learn, stimulated curiosity, and supported retention of scientific concepts. Based on these outcomes, we recommend teachers utilise this pedagogical strategy more frequently within the science classroom, as it has proven to be highly beneficial in supporting students’ understanding of complex and abstract concepts.

Throughout this lesson sequence, it was visibly clear that the stage 2 students were engaged and highly enjoyed the experience of embodying the solar system to learn about its key features. Students responded well to the idea of embodiment and displayed a strong understanding of rotations and revolutions. The kinaesthetic aspect of the learning sequence enabled students to make complex ideas like the orbits of different planets, concrete which supported their conceptual understanding of scientific ideas (Lindgren & Johnson-Glenberg, 2013; Shapiro & Stolz, 2019).

Conclusion

During embodied lessons, some students struggled with spatial awareness which was addressed by the classroom teacher through explicit modelling (AERO, 2023). The teacher used visual markers on the floor and provided step-by-step modelling on how to engage in the embodied experience. To avoid students being unsettled due to the interactive tasks, the teacher intentionally structured groups heterogeneously to promote productivity.

References

- Australian Education Research Organisation. (2023). Planning for classroom management: Practice guide. https://www.edresearch.edu.au/sites/default/files/2023-12/planning-for-classroom-management-aa.pdf

- Dolan, A. M. (2016). Place-based curriculum making: Devising a synthesis between primary geography and outdoor learning. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(1), 49-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1051563

- Hattan, C., & Alexander, P. A. (2020). Prior knowledge and its activation in elementary classroom discourse. Reading & Writing, 33(6), 1617–1647.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10022-8

- Hindman, A. H., Wasik, B. A., & Anderson, K. (2022). Using Turn and Talk to Develop Language: Observations in Early Classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 76(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.2113

- Karaman, P., & Büyükkıdık, S. (2023). Teachers’ Use of Open-ended Questions: A Mixed-methods Study. The Clearing House, 96(2), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2023.2166891

- Lindgren, R., & Johnson-Glenberg, M. (2013). Emboldened by Embodiment: Six Precepts for Research on Embodied Learning and Mixed Reality. Educational Researcher, 42(8), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X13511661

- Luo, Y., Jia, P., Liu, B., Lai, N. Y. G., Li, G., & Chai, W. S. (2025). Role-Playing as an Embodied Cognition Strategy to Enhance Learning Outcomes in the Empathize and Define Stages of Design Thinking Within Project-Based Design Courses. In B. K. Smith & M. Borge (Eds.), Learning and Collaboration Technologies (pp. 89–101). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-93564-0_6

- Mavilidi, M. F., Ouwehand, K., Schmidt, M., Pesce, C., Tomporowski, P. D., Okely, A., & Paas, F. (2022). Embodiment as a pedagogical tool to enhance learning. In S. A. Stolz (Ed.), The Body, Embodiment, and Education (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 183–203). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003142010-10

- Myhill, D., & Dunkin, F. (2005). Questioning Learning. Language and Education, 19(5), 415–427.https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780508668694

- NSW Education Standards Authority. (2024). Science and technology K–6 syllabus. NSW Curriculum.

- hapiro, L., & Stolz, S. (2019). Embodied cognition and education.

- Walter, H. A. (2018). Beyond Turn and Talk: Creating Discourse. Teaching Children Mathematics, 25(3), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.5951/teacchilmath.25.3.0180

- Way, J., Ginns, P., Preston, C., Niland, A., & Uptin, J. (2021). Embodied learning in early mathematics and science (ELEMS). Department of Education (NSW)/Strategic Research Fund.

- Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(4), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196322